Iran l’histoire du blé, du pain, de la pizza et des raviolis (photos&vidéos)

(✍️ENGLISH text under each French text)

Iran the History of wheat, bread, pizza and ravioli (photos&videos)

L’agriculture s’est développée à l’est de l’Iran vers 12 000 av. J.-C. Et les formes domestiques du blé apparaissent vers 10 500 avant J.-C.

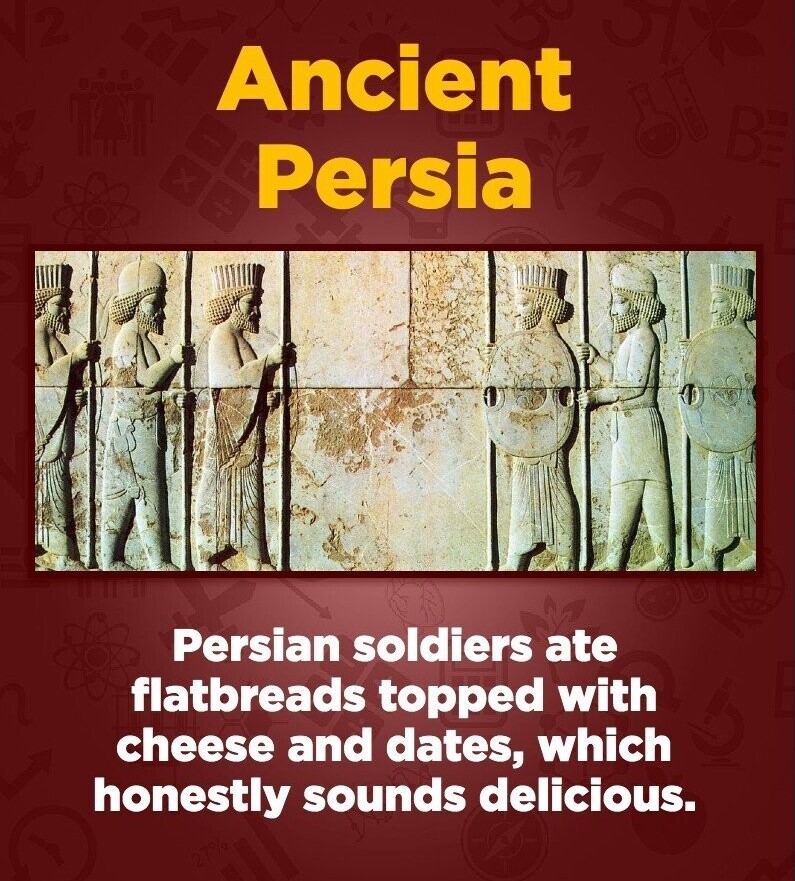

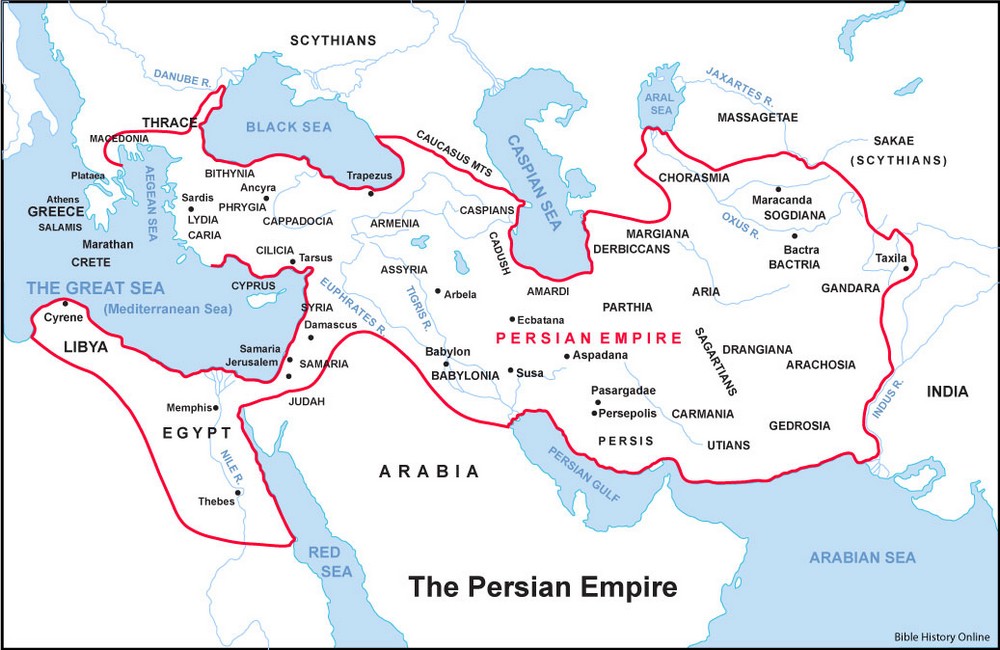

Le pain plat avec des garnitures dessus est considéré comme le premier style de pizza, apparu pendant l’Empire Iranien Achéménide (Empire Perse) 549 – 486 av. J.-C.

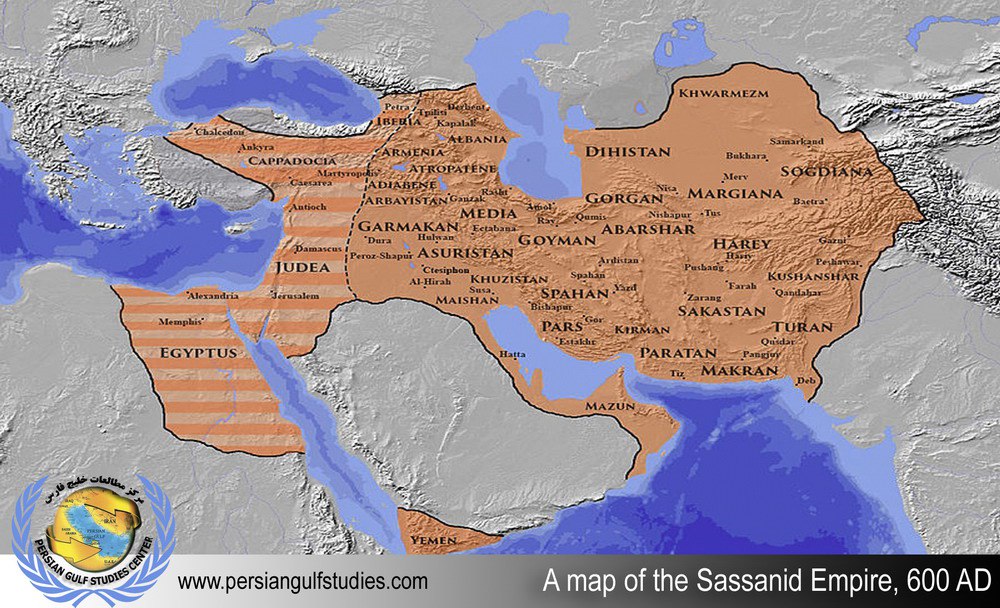

Et que les raviolis sont issus de la cuisine iranienne datant de l’Empire Iranien Ērānshahr (Empire Sassanide) 224 – 651 apr. J.-C.

La domestication du blé et de l’orge a révolutionné le mode de vie des tribus iraniennes des Monts Zagros.

Tous les aspects de la culture des céréales ont poussé les tribus à développer des méthodes de culture de plus en plus efficaces.

De l’irrigation (Qanat, classée par l’UNESCO en 2016) sous forme de canaux d’épandage de crues, de transport, de stockage, de préparation des aliments et de la commercialisation. (Les qanâts iraniens font 7,7 x la circonférence de la Terre !)

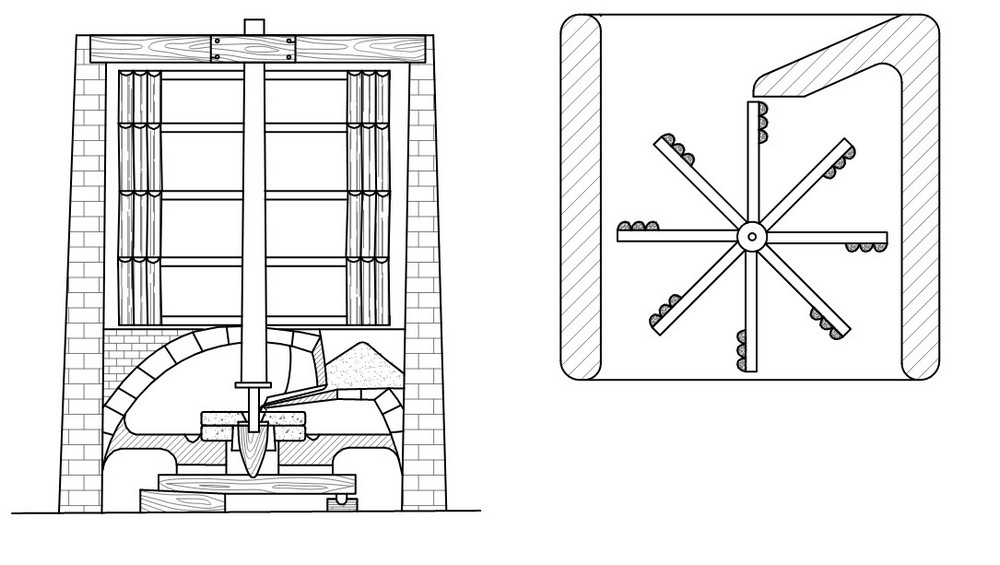

L’ingéniosité des anciens iraniens/persans va même développer les premiers moulins à vent pour but principal de broyer les graines comestibles ou de les tamiser il y a plus de 1 000 ans.

Les céréales ont d’abord été utilisées sous forme de bouillies crues, et certaines de ces bouillies étaient fermentées (qui deviendra la bière).

Photos:

1-Iran l’histoire du blé

2-Iran Moulins à vent

3-Iran Bière Godin Tepe

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Iran the History of wheat, bread, pizza and ravioli

Agriculture developed in eastern Iran around 12,000 BC. And domesticated forms of wheat appeared around 10,500 BC.

Flat bread with toppings on top is considered the first style of pizza, appearing during the Iranian Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) 549 – 486 BC.

And that ravioli originated from the Iranian cuisine dating back to the Iranian Empire Ērānshahr (Sassanid Empire) 224 – 651 AD.

The domestication of wheat and barley revolutionized the way of life of the Iranian tribes of the Zagros Mountains.

All aspects of cereal growing have led tribes to develop increasingly efficient cultivation methods.

From irrigation (Qanat, classified by UNESCO in 2016) in the form of flood channels, transport, storage, food preparation and commercialization. (Iranian qanats are 7.7 times the circumference of the Earth!)

The ingenuity of the ancient Iranians/Persians even led to the development of the first windmill, whose main purpose was to grind or sift edible seeds over 1,000 years ago.

Cereals were first used in the form of raw porridges, and some of these were fermented, (which became beer.)

Photos:

1-Iran the History of wheat

2-Iran Windmill

3- Iran Beer Godin Tepe

*

La position géographique de l’Iran en Asie, située à la croisée du Levant et du Caucase à l’ouest, et de l’Asie de l’Est et Centrale à l’est démontre des traces d’occupation humaine vieilles de 800 000 à 165 000 ans.

En effet, les fouilles archéologiques sur le Plateau Central Iranien et les montagnes du Zagros et de l’Alborz, ne manquent pas de surprendre et il reste encore beaucoup à découvrir.

-Liste des pays d’Asie (Iran)

https://www.cartograf.fr/liste_pays_asie.php

-Géographie de l’Iran

https://negah.fr/geographie-iran/

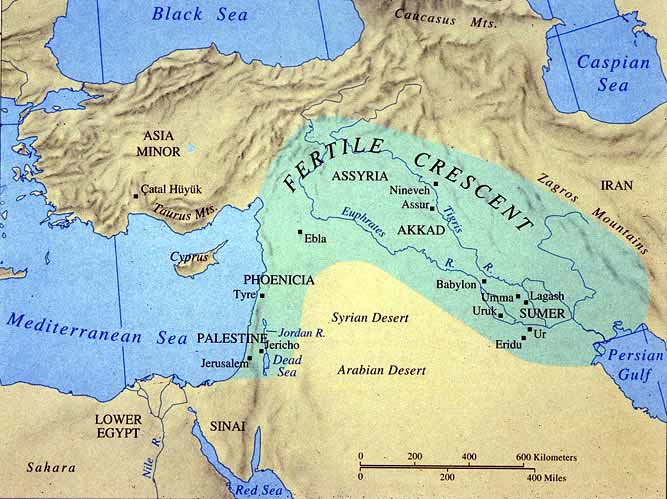

Au temps de la Mésopotamie les Monts Zagros séparaient les plaines alluviales de l’Assyrie et de la Babylonie des hauts plateaux iraniens.

Le Mont Zagros a fait prospérer des puissantes tribus comme les ancêtres de peuples tels que les Sumériens, (avant les sumériens, un peuple venu du Zagros de la période dite Ubaid (6500 avant J.-C, à 3750 av. J.-C.), va façonner la Mésopotamie.

Outre, le Mont Zagros a aussi fait prospérer des tribus telles que les Lullubis (du IIIe au IIe millénaire av. J.-C.), les Élamites (du IIIe au Ier millénaire av. J.-C.), les Gutis (vers 2218 à 2047 av. J.-C.), les Kassites (1800 av. J.-C., à 1000 av. J.-C.) et les Mitanni (de 1475 av. J.-C., à 1275 av. J.-C.)

Il est d’ailleurs dit que des grands monuments de Sumer et Babylonien en Mésopotamie étaient en partie fabriquées et décorées avec des matériaux provenant du Zagros. Les montagnes du Zagros étaient riches de plomb, d’argent et de l’or ainsi que du cuivre, qui pouvait être utilisé pour fabriquer des outils et objets.

-Le terme Mésopotamie et la position géographique

https://www.shorthistory.org/ancient-civilizations/mesopotamia/the-term-mesopotamia-and-geographical-position/

-Agriculture en Mesopotamie

https://fr-academic.com/dic.nsf/frwiki/62452

Le nom Zagros est dérivé du nom « Sagar-tians ». Les Sagarthiens étaient une ancienne tribu iranienne principalement des éleveurs nomades, élevant du bétail tel que des chevaux, des bovins et des moutons.

Outre, être une région riche en archéologies c’est aussi une région riche de légendes et de mythes fascinants. Selon des anciens récits persans, le Zagros était la Terre des Dieux, le Centre du Monde, d’alors.

Par ailleurs, les fameux chevaux niséens étaient originaires des plaines Niséenne dans le sud des montagnes du Zagros en Iran. La plaine niséenne était une plaine fertile habitée par les iraniens Mèdes de l’ancien royaume Mède (de 750 à 552 av. J.-C.)

Le nom Nisséen tire son origine de la région Nisàya dans l’ancienne Hegmataneh (connu sous le nom Grec Ecbatane), qui est depuis la province Hamadan, Iran.

Le cheval Nisséen de race exceptionnelle fut utilisé par les iraniens Mèdes, 750 – 552 av. J.-C., puis par les divers rois de l’Empire Iranien Achéménide (Empire Perse) 549 – 486 av. J.-C., ainsi que par les divers souverains de l’Empire Iranien Ērānshahr (Empire Sassanide) 224 – 651 apr. J.-C.

Les Niséens d’un blanc pur étaient les chevaux des Dieux et des Rois, des récits légendaires et mythiques ne manqueront pas sur ces chevaux blancs. Pour les autres chevaux Niséens, certains étaient tachetés, comme un léopard, ou dorés. D’autres étaient roux et bleus avec des couleurs plus foncées.

Le cheval Nisséen est une race extinctée.

-Le cheval a été domestiqué en Iran depuis plus de 6000 ans

https://primalderma.com/we-are-good-because-of-our-horses-the-post-office-and-ancient-persia/

-NISĀYA

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nisaya

-Le nisaen, une race de cheval iranien éteinte

http://www.teheran.ir/spip.php?article2778#gsc.tab=0

-Cheval de Nisean

http://horsehints.org/Breeds/NiseanExtinct.htm

-Le cheval royal de Nisean de l’ancienne Perse

https://ancientimes.blogspot.com/2020/04/the-royal-nisean-horse-of-ancient-persia.html

-Relief à deux chevaux, Iran Persépolis, Darius(522 – 486 av. J.-C.) Xerxès(486 – 465 av. J.-C.)

Les deux chevaux de char du fragment de Shumei sont rendus de manière exquise, avec une grande attention à la modélisation et à la finesse des détails des atours. Ils peuvent être identifiés comme des chevaux nésiens, une petite race compacte caractérisée par un cou fortement arqué et représentée à l’époque achéménide sur des reliefs en pierre, des sculptures architecturales et des objets précieux.

https://www.miho.jp/booth/html/artcon/00001351e.htm

-Les Chevaux du Ciel

https://www.parthia.com/parthia_horses_heaven.htm

Les montagnes du Zagros sont une chaîne de montagnes d’environ 1 500 km qui s’étend depuis l’ouest de l’Iran, de la province du Kordestan jusqu’au golfe Persique.

En ces temps passés il n’y avait pas de frontière comme aujourd’hui et certains pays actuels aux alentours n’existaient pas encore.

Actuellement bien que cette chaîne de montagnes soit principalement présente en Iran, les extrémités de cette gamme se répandent avec les frontières modernes de l’actuel Irak (ancienne Mésopotamie) et de l’actuelle Turquie (ancienne Anatolie).

Photos:

4-Le Zagros sur une tablette cunéiforme Babylonienne. Une route, une montagne et une rivière sont indiquées. (Musée Paris, Louvre)

https://www.livius.org/articles/place/zagros/

5-Carte Mésopotamie

https://www.rcboe.org/cms/lib/GA01903614/Centricity/Domain/1872/Ancient%20Mesopotamia%20Powerpoint%20SSWH1-2.pdf

6-Zone d’étude dans les montagnes du Zagros et de l’Elburz en Iran

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Study-area-in-the-Zagros-and-Elburz-Mountains-of-Iran-This-map-is-originally-created-by_fig1_330748320

7-Zagros Mountains

https://www.worldatlas.com/mountains/zagros-mountains.html

-ASAGARTA

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/asagarta

-La chaîne iranienne du Zagros

https://actugeologique.fr/2020/06/la-chaine-iranienne-du-zagros/

-Montagnes de l’Est : le Zagros central : perspective de la glyptique akkadien

https://www.hunara.org/article_176271.html

-Sédentarité et gestion des ressources au Néolithique du Zagros central

https://www.czap.org/

-Iran (Montagnes du Zagros) – Dôme de sel de Dashti (Jashak salt dome) : strates de sel rose et gris avec figures de dissolution

https://www.philippe-crochet.com/galerie/desert/details/209/iran-fevrier-2016-domes-de-sel/237008/vo-16-0350-legende

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Iran’s geographical position in Asia, at the crossroads of the Levant and the Caucasus to the west, and East and Central Asia to the east, shows traces of human occupation dating back 800,000 to 165,000 years.

Indeed, archaeological digs in Iran’s Central Plateau and the Zagros and Alborz mountains are full of surprises, and there’s still much to discover.

-List of Countries in Asia (Iran)

https://visaguide.world/asia/

-Geography of Iran

https://www.iranchamber.com/geography/geography.php

In Mesopotamian times, the Zagros Mountains separated the alluvial plains of Assyria and Babylonia from the Iranian highlands.

Mount Zagros gave rise to powerful tribes such as the ancestors of peoples like the Sumerians and later the Kassites, Gutis, Lullubis and Elamites.

It is said that some of the great monuments of Sumer and Babylon were made and decorated with materials from the Zagros. The Zagros mountains were rich in lead, silver and gold, as well as copper, which could be used to make tools and objects.

-The term Mesopotamia and geographical position

https://www.shorthistory.org/ancient-civilizations/mesopotamia/the-term-mesopotamia-and-geographical-position/

-Ancient Mesopotamian Agriculture

https://ancientmesopotamians.com/ancient-mesopotamian-agriculture.html

The name Zagros is derived from the name « Sagar-tians ». The Sagarthans were an ancient Iranian tribe dwelling on the Iranian plateau.

As well as being a region rich in archaeology, it is also a region rich in fascinating legends and myths. According to ancient Persian accounts, the Zagros was the Land of the Gods, the Center of the World at that time.

In addition, the famous Nisean horses originated from the Nisean plains in the southern Zagros mountains of Iran. The Nisean plain was a fertile plain inhabited by the Iranian Medes of the ancient Mede kingdom (750-552 BC).

The name Nisseen derives from the Nisàya region in ancient Hegmataneh (known by the Greek name Ecbatane), which is since the province of Hamadan, Iran.

The exceptional Nissian horse was used by the Iranian Medes, 750 – 552 BC, then by the various kings of the Iranian Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) 549 – 486 BC, as well as by the various rulers of the Iranian Ērānshahr Empire (Sassanid Empire) 224 – 651 AD.

The pure-white Niseans were the horses of Gods and Kings, and there’s no shortage of legendary and mythical tales about these white horses. As for the other Niséens horses, some were spotted, like a leopard, or golden. Others were red and blue with darker colors.

The Nissen horse is an extinct breed.

-Horses have been domesticated in Iran for over 6,000 years

https://primalderma.com/we-are-good-because-of-our-horses-the-post-office-and-ancient-persia/

-NISĀYA

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nisaya

-Nisean Horse

http://horsehints.org/Breeds/NiseanExtinct.htm

-The Royal Nisean Horse of Ancient Persia

https://ancientimes.blogspot.com/2020/04/the-royal-nisean-horse-of-ancient-persia.html

-Relief with Two Horses, Iran Persepolis, Darius(522 – 486B.C.) Xerxes(486 – 465 B.C.)

The two chariot horses of the Shumei fragment are exquisitely rendered, with great attention to modeling and the fine detail of trappings. They may be identified as Nesaean horses, a small compact breed characterized by a strongly arched neck and depicted during the Achaemenid period on stone reliefs, architectural sculpture, and precious objects.

https://www.miho.jp/booth/html/artcon/00001351e.htm

-The Horses of Heaven

https://www.parthia.com/parthia_horses_heaven.htm

The Zagros Mountains are a chain of mountains some 1,500 km long, stretching from western Iran in the province of Kordestan to the Persian Gulf.

In those days, there were no borders like there are today, and some of today’s neighbouring countries didn’t yet exist.

Currently, although this mountain range is mainly present in Iran, the extremities of this range spread with the modern borders of today’s Iraq (ancient Mesopotamia) and today’s Turkey (ancient Anatolia).

Photos:

4-Babylonian map of the western Zagros. A road, a mountain, and a river are indicated.

Museum Paris, Louvre

https://www.livius.org/articles/place/zagros/

5-Ancient Mesopotamia

https://www.rcboe.org/cms/lib/GA01903614/Centricity/Domain/1872/Ancient%20Mesopotamia%20Powerpoint%20SSWH1-2.pdf

6-Study-area-in-the-Zagros-and-Elburz-Mountains-of-Iran

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Study-area-in-the-Zagros-and-Elburz-Mountains-of-Iran-This-map-is-originally-created-by_fig1_330748320

7-Zagros Mountains

https://www.worldatlas.com/mountains/zagros-mountains.html

-ASAGARTA

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/asagarta

-Zagros Mountains

https://www.worldatlas.com/mountains/zagros-mountains.html

Eastern Mountains: Central Zagros Perspective on the Akkadian Glyptics

https://www.hunara.org/article_176271.html

-Sedentism and Resource Management in the Neolithic of the Central Zagros

https://www.czap.org/

-The central and northern Zagros during the Late Chalcolithic: An updated ceramic chronology based on recent fieldwork results in western Iran

https://journals.openedition.org/paleorient/366

-Salt Domes And Salt Glaciers of Zagros Mountains, Iran

https://themindcircle.com/salt-glaciers-iran/

*

Les plaines fertiles du mont Zagros permirent aux tribus iraniennes de prospérer en agriculture vers 12 000 av. J.-C. (Site archéologique Neolithic pré-potier de Chogha Golan que vous pouvez visiter lors de votre séjour en Iran).

Le blé a d’abord été récolté à l’état sauvage par les chasseurs-cueilleurs comme un produit de cueillette en source supplémentaire de nourriture.

Les céréales ont d’abord été utilisées sous forme de bouillies crues, et certaines de ces bouillies étaient fermentées (bière), plus ci-dessous.

Et les formes domestiques du blé apparaissent vers 10 500 av. J.C.

Les céréales (graines d’orge et de blé sauvage, ancêtres du blé domestiqué) étaient cassées, décortiquées, concassées et tamisées. Cette farine était ensuite mélangée à de l’eau pour former une pâte à cuire sur des braises ou des pierres chaudes.

L’innovation importante qui suivit fut la cuisson de la pâte vers 3 500 av. J.-C. Les premiers signes de cuisson du pain en Iran sont les traces de silo à blé proche de fours à double dôme.

Des tablettes d’argile indiquent que la brasserie était une occupation très importante en l’Iran il y a plus de 7 000 ans.

Photos:

8-Pain Traditionnel Iranien

9-Pain Traditionnel Iranien

-Un riche assemblage de fossiles et d’artefacts dans les contreforts des montagnes Zagros en Iran a révélé que les premiers habitants de la région ont commencé à cultiver des céréales pour l’agriculture il y a entre 12 000 et 9 800 ans.

La découverte implique que la transition de la recherche de nourriture à l’agriculture a eu lieu à peu près au même moment dans l’ensemble du Croissant fertile, et non dans une seule zone centrale du « berceau de la civilisation », comme on le pensait auparavant.

http://www.archeolog-home.com/pages/content/chogha-golan-iran-no-single-origin-for-agriculture-in-the-fertile-crescent.html

-Découverte de preuves de l’agriculture ancienne en Iran

De nouvelles recherches suggèrent que l’agriculture pourrait être apparue simultanément dans de nombreux endroits du Croissant fertile.

Des archéologues ont mis au jour des preuves de l’agriculture primitive sur un site vieux de 12 000 ans dans les montagnes du Zagros en Iran.

https://www.livescience.com/37963-agriculture-arose-eastern-fertile-crescent.html

-L’agriculture aurait été inventée pour la première fois par les habitants des monts Zagros, dans l’actuel Iran. Toutefois, elle serait aussi apparue simultanément dans d’autres régions du Croissant fertile.

https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/archeologie/l-agriculture-aurait-debute-dans-deux-populations-distinctes-du-moyen-orient-12392.php

-Les racines de l’agriculture se sont étendues à l’est de l’Iran

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/agricultures-roots-spread-east-iran

-Les premiers villages agricoles de l’est du plateau Iranien à la vallée de l’Indus

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003552122000607

-L’Iran, un des foyers de naissance de l’agriculture ?

L’analyse de plantes fossiles en Iran suggère que l’agriculture est apparue de façon quasi simultanée dedans tout le Croissant fertile, il y a 11 500 à 11 000 ans.

https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/archeologie/l-iran-un-des-foyers-de-naissance-de-l-agriculture-11674.php

-La culture et la domestication du blé et de l’orge en Iran, bref retour sur une longue histoire

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12229-020-09244-w

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

The fertile plains of Mount Zagros enabled Iranian tribes to prosper in agriculture around 12,000 BC. (The Neolithic pre-pottery archaeological site of Chogha Golan, which you can visit during your trip to Iran.)

Wheat was first harvested in the wild by hunter-gatherers as a supplementary food source.

Cereals were first used in the form of raw porridges, some of which were fermented (beer), more below.

And domesticated forms of wheat appeared around 10,500 BC.

Cereals (barley and wild wheat seeds, the ancestors of domesticated wheat) were broken, shelled, crushed and sieved. This flour was then mixed with water to form a dough to be cooked over hot coals or stones.

The next important innovation was the baking of dough around 3,500 BC. The first signs of bread baking in Iran are traces of wheat silos near a double-domed ovens.

Clay tablets indicate that brewing was a very important occupation in Iran over 7,000 years ago.

Photos:

8-Iran Traditional Flat Bread

9-Iran Traditional Flat Bread

-A rich assemblage of fossils and artifacts in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains in Iran has revealed that the early inhabitants of the region began cultivating cereal grains for agriculture between 12,000 and 9,800 years ago.

The discovery implies that the transition from foraging to farming took place at roughly the same time across the entire Fertile Crescent, not in a single core area of the « cradle of civilization, » as previously thought.

http://www.archeolog-home.com/pages/content/chogha-golan-iran-no-single-origin-for-agriculture-in-the-fertile-crescent.html

-Farming Got Hip In Iran Some 12,000 Years Ago, Ancient Seeds Reveal

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/07/08/198453031/farming-got-hip-in-iran-some-12-000-years-ago-ancient-seeds-reveal

-Two groups spread early agriculture

FOUNDING FARMERS A bone fragment from a 7,000-year-old farmer was discovered in this cave in the Zagros region of Iran. His DNA and the DNA of three other individuals from a second Iranian site revealed that two different groups were involved in early farming.

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/two-groups-spread-early-agriculture

-Agriculture’s roots spread east to Iran

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/agricultures-roots-spread-east-iran

-Iran, one of the birthplaces of agriculture?

Analysis of fossil plants in Iran suggests that agriculture appeared almost simultaneously throughout the Fertile Crescent between 11,500 and 11,000 years ago.

https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/archeologie/l-iran-un-des-foyers-de-naissance-de-l-agriculture-11674.php

-Evidence of Ancient Farming in Iran Discovered

Agriculture may have arisen simultaneously in many places throughout the Fertile Crescent, new research suggests.

Archaeologists have unearthed evidence of early agriculture at a 12,000-year-old site in the Zagros Mountains in Iran.

https://www.livescience.com/37963-agriculture-arose-eastern-fertile-crescent.html

-The cultivation and domestication of wheat and barley in Iran, brief review of a long history

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12229-020-09244-w

*

Bière

Au sujet de la bière, c’est sur le site archéologique de Godin Tepe dans le Central du Zagros en Iran que la première bière d’orge chimiquement confirmé fut découverte, datée d’entre 3 500 et 3 100 av. J.-C.

Godin Tepe est un site visitable, ne pas manquer d’y faire un tour.

Photo:

10-Godin-Tepe assemblage de jar de bière et de sherd portant du oxalate de calcium.

(Laboratoire du Musée royal de l’Ontario)

-Détection d’une bière brassée à Godin Tepe (Iran) il y a 5500 ans. – Études sur la bière

Sur le site de Godin Tepe (nord des monts Zagros à la frontière irano-irakienne, vallée de Kangavar, province de Kermanshah), un tesson de jarre a révélé la présence d’ions d’oxalate de calcium dans les résidus jaunâtres de ses rainures.

Cette signature de la fermentation alcoolique, associée aux grains d’orge carbonisés découverts dans la même pièce, démontre sans ambiguïté la destination de cette jarre datée de 3500-3100 av. n. ère : (une jarre à bière).

https://beer-studies.com/fr/Histoire_generale/Naissance-brasserie/Bieres-archaiques/Godin-Tepe

-GODIN TEPE

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/godin

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Beer

About beer, at the archaeological site of Godin Tepe in Iran’s Central Zagros that the first chemically confirmed barley beer was discovered, dated between 3,500 and 3,100 BC.

Godin Tepe is a site worth visiting.

Photo:

10-Godin-Tepe-assemblage_of_beer_jar_and_sherd_bearing_calcium_oxalate_

(Royal Ontario Museum Lab)

-Detection of a beer brewed at Godin Tepe (Iran) 5500 years ago. – Beer Studies

At the Godin Tepe site (north of the Zagros Mountains on the Iranian-Iraqi border, valley of Kangavar, province of Kermanshah), a shard of jar revealed the presence of calcium oxalate ions in the yellowish residues of its grooves.

This signature of alcoholic fermentation, together with the charred barley grains discovered in the same room of a fortress, clearly demonstrates the purpose of this jar dated 3500-3100 BC: (a beer jar).

https://beer-studies.com/en/world-history/Birth-of-brewing/Archaic-beers/Godin-Tepe

-GODIN TEPE

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/godin

*

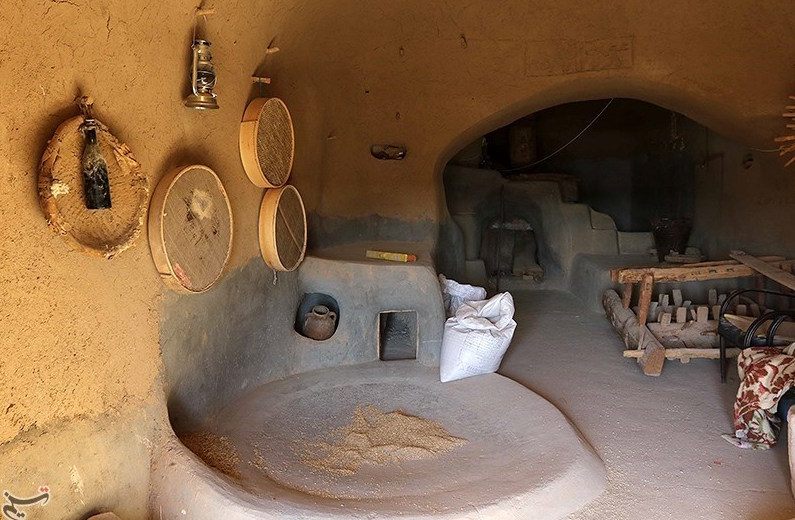

Il va sans dire que la domestication du blé et de l’orge a révolutionné le mode de vie des tribus iraniennes du mont Zagros .

Tous les aspects de la culture des céréales ont poussé les tribus à développer des méthodes de culture de plus en plus efficaces.

De l’irrigation (appelée Qanat, classée par l’UNESCO en 2016), sous forme de canaux d’épandage de crues, ces canaux souterrains qui s’étendent souvent sur des kilomètres puisaient dans les aquifères souterrains, amenant à la surface de l’eau vitale pour l’agriculture et l’usage domestique.

Du transport et de stockage avec des structures appelées en persan Tapu. Tapu était une structure de stockage fait de boue d’une hauteur de deux à trois mètres et d’une largeur d’un mètre et demi, séché en plein air et par le soleil pour consolider la structure.

Sans oublié toute l’organisation de préparation des aliments et de la commercialisation.

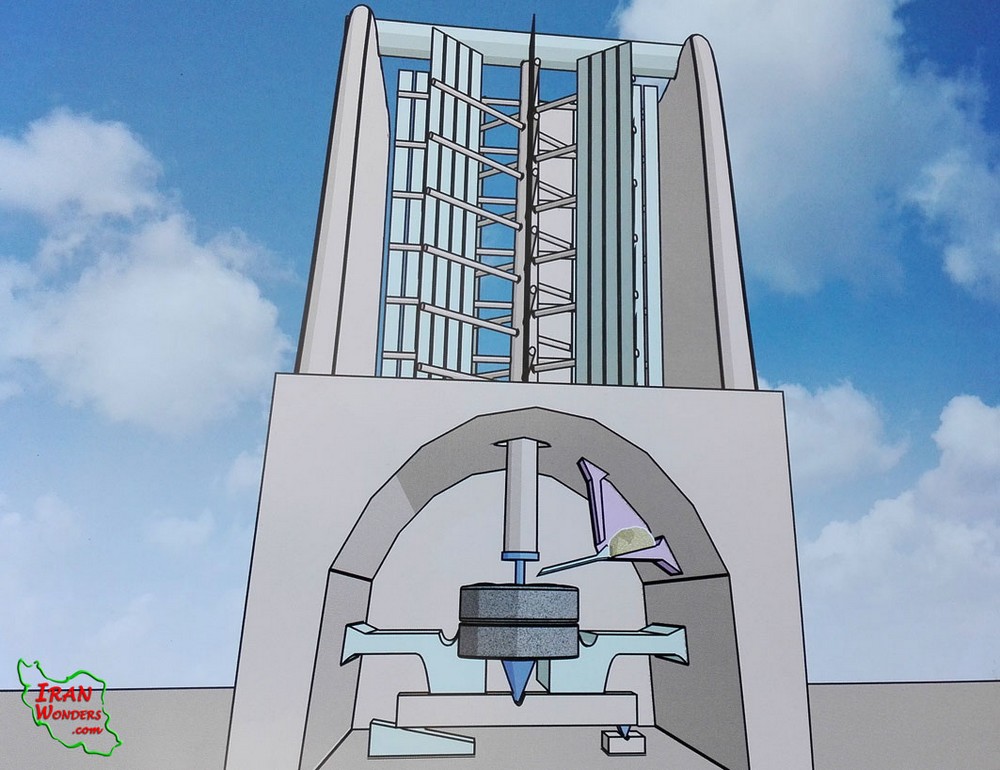

Et l’ingéniosité des iraniens va même cré les premiers moulins à vent pour but principal de broyer les graines comestibles ou de les tamiser il y a plus de 1000 ans.

Le mot Qanât est un vieux mot d’origine akkadienne, dérivé du mot qanat (roseau) d’où vient aussi le mot canna et canal. La langue akkadienne fut parlée en Mésopotamie du début du IIIᵉ jusqu’au Iᵉʳ millénaire av. J.-C.

En persan ça se dit Kariz, qui est dérivé du mot antérieur Kahriz. Kahriz signifie verser des pailles pour tester l’écoulement de l’eau.

Ce qui est impressionnant tout de même, les qanâts iraniens font 7,7 x la circonférence de la Terre ! Si l’on considère que la longueur moyenne de chaque qanât est de 6 km dans la plupart des régions du pays, la longueur totale des 30 000 systèmes de qanât (potentiellement exploitables aujourd’hui) est d’environ 310 800 km, soit environ 7,7 fois la circonférence de la Terre ou 6/7 de la distance Terre-Lune !

Toujours utilisés aujourd’hui en Iran, les qanâts fournissent environ 7,6 milliards de m3, soit 15 % du total des besoins en eau du pays.

Par ailleurs, il est dit que le plus long qanat au monde se situe en Iran. (Ne manquez de visiter ces qanâts lors de votre passage en Iran).

Outre, il y a aussi l’invention de l’horloge à eau dans les qanâts d’Iran.

Dès 500 av. J.-C., pour déterminer une répartition équitable des ressources d’irrigation entre les agriculteurs, un système d’horloge à eau dans sa forme la plus élémentaire fut inventée, en utilisant deux bols, l’un imbriqué dans l’autre.

Le bol extérieur est rempli d’eau; Le bol intérieur vide a un trou au fond qui permet à un débit d’eau contrôlé de s’infiltrer. Une fois que le bol intérieur s’est rempli d’eau, il est vidé et placé à nouveau à la surface de l’eau jusqu’à ce qu’il coule et ainsi de suite.

Le poste de chronométreur était important et soumis à la surveillance d’autres anciens du village pour assurer la parité.

Photos:

11-Qanats Gonabad Iran

12-Qanats Gonabad Iran

https://escapefromtehran.com/authentic-iran-travel-tour/iran-qanat-khorasan-gonabad/

13-Ancienne horloge à eau persane

https://www.pbase.com/image/156496180

14-Ancienne horloge à eau persane

-Site du patrimoine mondial de Gonabad Qasabeh Qanat

http://www.qasabehqanat.com/Index-en.aspx

-Qasabe Qanat de Gonabad (Le chef-d’œuvre de l’approvisionnement en eau dans l’Iran ancien)

https://iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/40-qasabe-qanat-of-gonabad-the-masterpiece-of-water-supply-in-ancient-iran/

-Le qanat perse – UNESCO

https://whc.unesco.org/fr/list/1506/

-Les qanâts d’Iran inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial

http://www.teheran.ir/spip.php?article2307#gsc.tab=0

-Les aqueducs de l’Iran

La découverte de conduits souterrains dans un certain nombre de sites romains antiques a conduit certains archéologues modernes à supposer que les Romains avaient inventé le système qanat.

Les documents écrits et les fouilles récentes ne laissent cependant aucun doute sur le fait que l’Iran ancien (la Perse) était son véritable lieu de naissance.

Dès le VIIe siècle av. J.-C., le roi assyrien Sargon II rapporta qu’au cours d’une campagne en Perse, il avait trouvé un système souterrain de captage d’eau près du lac d’Ourmia. Son fils, le roi Sennachérib, a appliqué le « secret » de l’utilisation de conduits souterrains dans la construction d’un système d’irrigation autour de Ninive, et il a construit un qanat sur le modèle persan pour fournir de l’eau à la ville d’Arbela.

Les inscriptions égyptiennes révèlent que les Perses ont donné l’idée à l’Égypte après que Darius Ier ait conquis ce pays en 518 av. J.-C.

https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/ancient-prehistory-651-a-d/achaemenids/the-aqueducts-of-iran/

-10 qanats iraniens uniques et remarquables

Il y a plus de 3 000 ans, les agriculteurs iraniens des régions arides ont créé des qanats, des canaux souterrains pour transporter l’eau des sources à leurs champs. Aujourd’hui, dix des 40 000 qanats actifs en Iran sont reconnus comme sites du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO. Ici, nous vous présentons ces remarquables qanats.

https://incredibleiran.com/blog/10-unique-and-remarkable-iranian-qanats/

-Les Qanats

L’adaptation de l’architecture traditionnelle en Iran au climat désertique : une belle exploitation des maigres ressources en eau combinée à des espaces de vie ingénieusement conçus

http://frederic-morin-salome.fr/Iran-qanat.html

-Qanat : l’ancien système d’irrigation iranien le plus remarquable

https://www.academia.edu/3731918/Qanat_Iranians_Most_Remark_Ancient_Irrigation_System

-Le qanât, un prodige de technologie hydraulique

https://tourisme-iran.fr/le-qanat-un-prodige-de-technologie-hydraulique/

(Vidéo) Un qanat est un canal couterrain utilisé pour déplacer l’eau à la surface pour l’irrigation et sa consommation par l’homme. Le plus grand du monde se situe en Iran.

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Clearly, the domestication of wheat and barley revolutionized the way of life of the Iranian tribes of Mount Zagros.

All aspects of cereal growing have led tribes to develop increasingly efficient cultivation methods.

From irrigation (called Qanat, classified by UNESCO in 2016), in the form of floodways, these underground canals that often stretch for kilometers drew on underground aquifers, bringing vital water to the surface for agriculture and domestic use.

Of transport and storage with structures called Tapu in Persian. Tapu was a storage structure made of mud two to three meters high and one and a half meters wide, dried in the open air and by the sun to consolidate the structure.

Not to mention the entire food preparation and marketing organization.

And the ingenuity of the Iranians went to create the first windmills, whose main purpose was to grind or sift edible seeds, over 1,000 years ago.

The word Qanât is an old word of Akkadian origin, derived from the word qanat (reed) from which also comes the word canna and canal. The Akkadian language was spoken in Mesopotamia from the early IIIᵉ to the Iᵉʳ millennium BC.

In Persian it’s called Kariz, which is derived from the earlier word Kahriz. Kahriz means pouring straws to test the flow of water.

Amazingly, Iranian qanats are 7.7 times the circumference of the Earth!

If we consider that the average length of each qanât is 6 km in most parts of the country, the total length of the 30,000 qanât systems (potentially exploitable today) is around 310,800 km, or around 7.7 times the circumference of the Earth, or 6/7 of the Earth-Moon distance!

Still in use today in Iran, qanâts supply around 7.6 billion m3, or 15% of the country’s total water requirements.

The longest qanat in the world is said to be in Iran (don’t miss visiting these qanats when you’re in Iran).

In addition, the invention of the water clock in the qanâts of Iran.

As early as 500 BC, to determine an equitable distribution of irrigation resources among farmers, a water clock system in its most basic form was invented, using two bowls, one nested inside the other.

The outer bowl is filled with water; the empty inner bowl has a hole in the bottom which allows a controlled flow of water to seep through. Once the inner bowl has filled with water, it is emptied and placed back on the surface of the water until it sinks, and so on.

The position of timekeeper was an important one, subject to the supervision of other village elders to ensure parity.

Photos:

11-Qanats Gonabad Iran

12-Qanats Gonabad Iran

https://escapefromtehran.com/authentic-iran-travel-tour/iran-qanat-khorasan-gonabad/

13-Ancient Persian Water Clock

https://www.pbase.com/image/156496180

14-Ancient Persian Water Clock

-Gonabad Qasabeh Qanat World Heritage Site

http://www.qasabehqanat.com/Index-en.aspx

-Qasabe Qanat of Gonabad (The masterpiece of water supply in ancient Iran)

https://iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/40-qasabe-qanat-of-gonabad-the-masterpiece-of-water-supply-in-ancient-iran/

-The Persian Qanat – UNESCO

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1506/

-Discoveries of underground conduits in a number of ancient Roman sites led some modern archaeologists to suppose the Romans had invented the qanat system.

Written records and recent excavations leave no doubt, however, that ancient Iran (Persia) was its actual birthplace.

As early as the seventh century B.C. the Assyrian king Sargon II reported that during a campaign in Persia he had found an underground system for tapping water in operation near Lake Urmia. His son, King Sennacherib, applied the “secret” of using underground conduits in building an irrigation system around Nineveh, and he constructed a qanat on the Persian model to supply water for the city of Arbela.

Egyptian inscriptions disclose that the Persians donated the idea to Egypt after Darius I conquered that country in 518 B.C.

https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/ancient-prehistory-651-a-d/achaemenids/the-aqueducts-of-iran/

-QANATS FROM IRAN

https://www.ideassonline.org/public/pdf/IRAN-Qanats-ENG.pdf

-Qanat Iranian’s Most Remark Ancient Irrigation System

https://www.academia.edu/3731918/Qanat_Iranians_Most_Remark_Ancient_Irrigation_System

-10 Unique and Remarkable Iranian Qanats

Over 3,000 years ago, Iranian farmers in arid regions created qanats, underground channels to transport water from springs to their fields. Today, ten of the 40,000 active qanats in Iran are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites. Here, we introduce these remarkable qanats.

https://incredibleiran.com/blog/10-unique-and-remarkable-iranian-qanats/

(Video )The Persian Qanat

*

Les moulins à vent

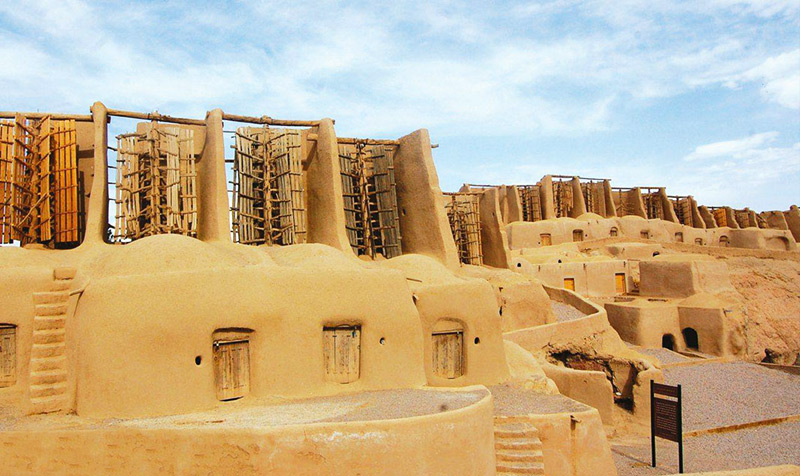

L’histoire des anciens moulins à vent en Iran remonte de 1500 – 1000 ans.

Ses structures remarquables ont été construites dans l’ancien village de Nashtifan, situé dans les parties méridionales de la province de Khorasan mais il y en a aussi dans des anciens villages comme Nehbandan, Khaf, Khargard et Barabad.

Cependant, parmi ces endroits, seuls ceux à Nashtifan ont survécu au fil des siècles, certains d’entre eux sont encore symboliquement utilisés pour produire de la farine selon des méthodes traditionnelles, que vous pouvez visiter lors de votre séjour en Iran.

Le petit village de Nashtifan a longtemps été une étape majeure sur l’ancienne Route de la Soie pendant l’Empire Iranien Achéménide 549 – 486 av. J.-C., (Empire Perse).

Par les locaux, la région est bien connue pour ces vents puissants.

Ces vents forts ont alimenté la créativité industrielle de la région pendant des siècles comme ces moulins à vent. Le but principal de ces moulins à vent était de broyer les graines comestibles ou de les tamiser.

Ce vent est aussi appelé « vent de 120 jours » parce que le vent souffle continûment jour et nuit durant les 4 mois les plus chauds de l’année.

Le nom du village Nashtifan

Selon certains, son nom est formé des deux mots Nash et Tifân. Le premier serait une prononciation locale du mot Nish (piqûre), et Tifân une prononciation locale de Toufân (tempête). Le nom de Nashtifân résumerait bien, dans ce cas, sa situation géographique, au centre d’une zone de vents et de tempêtes.

Cette dénomination pourrait aussi être une allusion à la piqûre des nombreuses espèces venimeuses, reptiles ou arachnides, qui peuplent cette région sèche et chaude.

Ces moulins à vent étaient principalement construits avec des briques de terre, boue séchée, du bois et de la paille.

Le bâtiment principal se compose de deux étages. Le rez-de-chaussée, qui comprend l’essentiel de l’édifice avec une grande meule de pierre, est la partie centrale du moulin où se fait le travail.

Une partie du rez-de-chaussée est dédiée à la réserve des graines, tandis que le deuxième étage comprend les pales verticales du moulin. Les pales du moulin sont construites en bois. Légères, elles se déplacent facilement horizontalement et font tourner la grande meule du sous-sol.

Les moulins étaient généralement construits côte à côte pour offrir une meilleure résistance au Vent des Cent-vingt jours.

Les moulins étaient bâtis dans le sens opposé au vent. La meule du moulin était lourde, et il fallait une pression importante pour la faire marcher. La force du vent était donc importante, mais aussi sa direction, pour qu’il exerce une force de traction maximum dans les pales. Lorsque le vent souffle, les lames se déplacent et font tourner le levier vertical actionnant la meule – un système simple et écologique.

Les vibrations générées par cette rotation déplacent progressivement les grains de leur récipient de stockage vers les moulins à grains, ce qui entraîne la production de farine.

Photos:

15-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

Hadidehghanpour, CC BY-SA 4.0.

16-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

17-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

18-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

19-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

20-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

21-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

22-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

23-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

24-Iran Nashtifân moulins à vent

https://www.iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/66-nashtifan-windmills/

-Moulin à vent Persan

http://lezart.free.fr/moulin19.htm

-Asbad : moulins à vents et hydrauliques souterrains

L’adaptation de l’architecture traditionnelle en Iran au climat désertique : une belle exploitation des maigres ressources en eau combinée à des espaces de vie ingénieusement conçus

http://frederic-morin-salome.fr/Iran-moulins.html

-Les moulins à vent millénaires de Nashtifan (Iran)

https://fdmf.fr/les-moulins-a-vent-millenaires-de-nashtifan-iran/

-Anciens moulins à vent de Nashtifan

https://thebrainchamber.com/ancient-windmills-of-nashtifan/

-Moulins à vent de Nashtifan (symbole de la technologie dans l’Iran ancien)

https://www.iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/66-nashtifan-windmills/

(Vidéo) Les moulins à vent de Nashtifan vieux de 1 000 ans

Dans le petit village de Nashtifan, en Iran, certains des plus anciens moulins à vent du monde, avec ce qui est peut-être le plus ancien moulin à vent du monde, tournent encore. De National Geographic:

Faits d’argile naturelle, de paille et de bois, les moulins à vent moudent le grain pour la farine depuis environ 1 000 ans. La conception de l’axe vertical est probablement similaire aux moulins à vent qui ont été inventés par les Perses vers 500 de notre ère, une conception qui s’est lentement répandue dans le monde et qui a ensuite été adaptée par les Hollandais et d’autres.

Le nom d’origine de Nashtifan était Nish Toofan, ce qui signifie « piqûre de tempête », une référence aux vents forts qui soufflent dans la région.

(Vidéo) Bien qu’elle soit reconnue comme un site du patrimoine national, cette technologie ancienne n’est entretenue que par une seule personne, Haj Ali Mohammad Etebari, un gardien âgé sans apprentis.

Il est présenté dans la vidéo du National Geographic ci-dessus, ainsi que dans ce court métrage documentaire de l’International Wood Culture Society:

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Windmills

The history of ancient windmills in Iran dates back 1500 – 1000 years ago.

Its remarkable structures were built in the ancient village of Nashtifan, located in the southern parts of Khorasan province, but there are also other in ancient villages such as Nehbandan, Khaf, Khargard and Barabad.

But among these places, only those in Nashtifan have survived over the centuries, some are still symbolically used to produce flour using traditional methods, which you can visit during your stay in Iran.

The small village of Nashtifan has long been a major stopover on the ancient Silk Road during the Iranian Achaemenid Empire 549 – 486 BC, (Persian Empire).

Locals know the area very well for its powerful winds.

These strong winds have fueled the region’s industrial creativity for centuries, like these windmills. The main purpose of these windmills was to grind or sift edible seeds.

This wind is also called the “120-day wind” because it blows continuously day and night during the 4 hottest months of the year.

The village name Nashtifan

According to some, its name is formed from the two words Nash and Tifân. The first is a local pronunciation of the word Nish (sting), and Tifân a local pronunciation of Toufân (storm).

In this case, Nashtifân’s name sums up its geographical location, at the center of a zone of winds and storms.

This name could also be an allusion to the bites of the many venomous reptiles and arachnids that inhabit this dry, warm region.

These windmills were mainly built with mud bricks, dried mud, wood and straw.

The main building has two floors. The first floor, which comprises the bulk of the building with a large stone millstone, is the central part of the mill where the work is done.

Part of the first floor is dedicated to seed storage, while the second floor houses the mill’s vertical blades.

The mill’s blades are made of wood. Lightweight, they move easily horizontally and turn the large grinding wheel in the basement. The mills were generally built side by side to offer greater resistance to the Hundred and Twenty Days Wind. Mills were built against the wind. The millstone was heavy, and required considerable pressure to operate.

Wind strength was therefore important, as was wind direction, to ensure maximum traction on the blades. When the wind blows, the blades move and turn the vertical lever that operates the grinding wheel – a simple, environmentally-friendly system.

The vibrations generated by this rotation gradually move the grain from its storage container to the grain mills, resulting in the production of flour.

Photos:

15-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

Hadidehghanpour, CC BY-SA 4.0.

16-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

17-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

18-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

19-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

20-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

21-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

22-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

23-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

24-Iran Nashtifân Windmills

https://www.iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/66-nashtifan-windmills/

-Persan windmill

http://lezart.free.fr/moulin19.htm

-Asbad : windmills and underground hydraulic mills

The adaptation of traditional Iranian architecture to the desert climate: a beautiful use of scarce water resources combined with ingeniously designed living spaces.

http://frederic-morin-salome.fr/Iran-moulins.html

-The thousand-year-old windmills of Nashtifan (Iran)

https://fdmf.fr/les-moulins-a-vent-millenaires-de-nashtifan-iran/

-Ancient-Windmills-of-Nashtifan-

https://thebrainchamber.com/ancient-windmills-of-nashtifan/

-Nashtifan Windmills (The symbol of technology in ancient Iran)

https://www.iranwonders.com/en/articles-en/66-nashtifan-windmills/

(Video) The 1,000 year old windmills of Nashtifan

In the small village of Nashtifan, Iran, some of the oldest windmills in the world, with what may be the earliest windmill design in the world, still spin. From National Geographic:

Made of natural clay, straw, and wood, the windmills have been milling grain for flour for an estimated 1,000 years. The vertical axis design is probably similar to the windmills that were invented by the Persians around 500 C.E.—a design that slowly spread through the world and which was later adapted by the Dutch and others.

Nashtifan’s original name was Nish Toofan, meaning ‘storm’s sting,’ a reference to the strong winds that blow through the area:

Though it’s recognized as a national heritage site, the ancient technology is tended to by only one person, Haj Ali Mohammad Etebari, an elderly custodian with no apprentices.

He’s featured in the National Geographic vid above, as well as this documentary short by the International Wood Culture Society:

*

Pizza

Les premiers styles de pizza sont apparus pendant l’Empire Iranien Achéménide (Empire Perse) 549 – 486 av. J.-C.

A l’époque de l’Empire Achéménide, les soldats de Darius le Grand cuisaient une forme de pain plat et le recouvraient de dattes et de fromages.

Il est dit que les soldats Achéménides utilisaient leurs boucliers de combat en métal, facilement chauffé par les flammes, étalaient de la pâte pour le cuire et qu’ils garnissaient ensuite le pain, puis le recouvert d’huile d’olive.

Ce plat vital et simple fait par les soldats de l’Empire Achéménide donnera l’idée aux envahisseurs d’Alexande de Macédoine en 334 av. J.-C., d’en faire de même. Et quand les soldats Macédoniens sont rentrés chez eux en Macédonie, ils ont introduit ce plat qui s’est vite transmis dans le monde de la Grèce antique.

Et plus tard dus à la longue guerre entre l’Empire Romain et l’Empire Perse, les soldats romains voyants comment les soldats de l’Empire Perse se nourrissaient, ils en feront pareil.

Mais ce n’est qu’au 18ème siècle de notre ère qu’en Italie des morceaux de pain plat appelé Pizza a commencé à être vendu dans les rues. Cependant, ces tranches de pain n’étaient garnies de rien. Les tranches de pain plates étaient principalement vendues à Naples car elles étaient bon marché à fabriquer.

La pizza va gagner en popularité parmi les personnes qui visitaient Naples, comme en 1889 quand la reine Margherita de Savoie accompagnée de son époux, visita l’Italie. Pendant son séjour, la reine Margherita découvre que beaucoup de gens, en particulier les paysans pauvres, aimaient manger cette grande tranche de pain plate. Par curiosité, la reine Margherita a décidé de goûter ce pain, et à la surprise de beaucoup de gens, la reine l’a adoré.

Ainsi, en l’honneur de la reine Margherita, une pizza unique et spéciale avec des garnitures de tomates, du basilic frais et du fromage représentant les couleurs du drapeau italien sera nommée Margherita.

C’est comme ça que des variantes de pizza ont commencé à être fabriquées dans diverses régions d’Italie, puis la pizza italienne sera connue dans le monde entier.

Photos:

25-The Internationally Confusing History of Pizza

https://www.cracked.com/article_35377_the-internationally-confusing-history-of-pizza.html

26-L’empire Perse

Qui a inventé la pizza ?

1) Les Perses

Datant du 6ème siècle avant JC, l’Empire perse consommait une variante de la pizza.

Sous le roi Darius Ier et sa vaste armée, les troupes devaient trouver un moyen de nourrir un grand nombre d’entre elles pour rester assez fortes pour repousser les ennemis. À l’aide de leurs boucliers de combat en métal, facilement chauffés par les flammes, les hommes ont commencé à cuire du pain plat garni de fromage.

Le résultat était un plat qui ressemble beaucoup à ce à quoi ressemblait la pizza aujourd’hui.

2) Les Grecs

Les Perses avaient des États alliés amis, y compris certaines régions de Grèce, tout au long et au-delà de la guerre (et les Perses en ont combattu beaucoup).

En tant qu’amis, les Perses voulaient s’assurer que leurs voisins étaient bien nourris. Partager leur recette simple et rapide avec les Grecs était logique. Leurs pains plats avec du fromage et d’autres garnitures prenaient peu de temps à cuire mais étaient également copieux. Beaucoup pensent que c’est ainsi que la pizza ancienne a commencé à se répandre dans le monde entier.

Les Grecs de l’Antiquité, lorsqu’ils étaient à la maison, avaient plus de temps pour expérimenter le plat afin de le rendre plus savoureux. C’est à ce moment-là qu’ils ont introduit des garnitures comme des herbes, de l’ail et des oignons.

3) Les Romains

Les Romains de l’Antiquité consommaient également une variété de pizzas, en particulier les Romains juifs qui mangeaient des biscuits casher pendant la Pâque.

L’utilisation du pain pascal italien, que beaucoup appellent aujourd’hui pain de Pâques. Bien que la liste des garnitures, le cas échéant, soit inconnue, le pain est sans aucun doute similaire à la base de pizzas que nous voyons aujourd’hui. Cependant, à son apogée, l’Empire romain s’étendait sur la majeure partie de l’Europe moderne et sur certaines régions du Moyen-Orient et de l’Afrique.

Tout au long de la vie de l’Empire, on a pensé que les populations des îles Baléares, des Balkans, du Levant, de la Catalogne et de Valence fabriquaient toutes une forme de pizza.

4) Méditerranées antiques

Les Méditerranéens de l’Antiquité mangeaient également une version de la « pizza ». Ils consommaient une grande quantité de focaccia, du pain plat au levain. Aujourd’hui, beaucoup l’appellent « pizza bianca » ou « pizza blanche ». Le plat était à la fois salé et sucré et était garni de romarin, de basilic, de sauge et de sel.

5) Autres mentions notables

Étant donné que le pain plat avec garnitures est considéré comme la recette de base de la pizza, il est important de noter que d’innombrables autres régions du monde consommaient des aliments très similaires. Ces populations comprennent le bing chinois, qui consiste en une base de pain plate ou circulaire. Les Indiens ont mangé du paratha, un pain gras mélangé à des pommes de terre épicées, un mélange vibrant de légumes, de viande, etc. Ils ajoutaient souvent des currys et des œufs au plat dans les portions du plat.

De plus, les populations remontant à l’ancienne Asie du Sud / centrale, celles d’origine finlandaise, l’Allemagne et la France ont toutes mangé des versions de pain plat avec garniture ou garniture pendant plusieurs centaines d’années.

https://www.hungryhowies.com/article/who-invented-pizza-0

-Comment faire cuire une pizza sur un bouclier comme un soldat persan de 600 avant JC.

https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-middle-east/persian-empire

-Les Perses de l’Antiquité ont inventé la pizza

https://sdmcphail.com/2016/10/12/ancient-persians-invented-pizza/

-Au VIe siècle, à l’époque de l’Empire perse, les soldats de Darius le Grand cuisaient une forme de pain et le recouvraient de dattes et de fromage.

https://ottavio.ca/en/the-history-of-pizza/

-PIZZA, HISTOIRE ET LÉGENDES

https://www.lebaccanti.com/en/ba/pizza-history-and-legends-11261

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Pizza

The first pizza styles appeared during the Iranian Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) 549 – 486 BC.

In the days of the Achaemenid Empire, the soldiers of Darius the Great baked a form of flatbread and covered it with dates and cheese.

It is said that Achaemenid soldiers used their metal battle shields, which were easily heated by flames, spread dough to bake it and then garnished the bread, covering it with olive oil.

This simple, vital dish made by soldiers of the Achaemenid Empire inspired the invaders of Alexander of Macedonia in 334 BC to do the same. And when the Macedonian soldiers returned home to Macedonia, they introduced this dish, which soon spread throughout the ancient Greek world.

And later, during the long war between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire, Roman soldiers saw how the soldiers of the Persian Empire fed themselves, and did the same.

But in Italy, it wasn’t until the 18th century AD that pieces of flat bread called Pizza began to be sold on the streets. However, these slices of bread were not topped with anything. Flat bread slices were mainly sold in Naples, as they were cheap to make.

Pizza gained popularity among visitors to Naples, like in 1889 when Queen Margherita of Savoy and her husband visited Italy. During her stay, Queen Margherita discovered that many people, especially poor peasants, liked to eat this large slice of flat bread. Out of curiosity, Queen Margherita decided to taste this bread, and to the surprise of many, the queen loved it.

Thus, in honor of Queen Margherita, a unique and special pizza with tomato toppings, fresh basil and cheese representing the colors of the Italian flag will be named Margherita.

That’s how pizza variants began to be made in various regions of Italy, and then Italian pizza became known worldwide.

Photos:

25-The Internationally Confusing History of Pizza

https://www.cracked.com/article_35377_the-internationally-confusing-history-of-pizza.html

26-The Persian Empire

Who Invented Pizza?

1) The Persians

Dating back to the 6th century BC, the Persian Empire consumed a variation of pizza. Under King Darius I and his vast army, the troops needed to find a way to feed large numbers of themselves to stay strong enough to ward off enemies. Using their metal battle shields, easily heated by flame, the men began to bake flatbread with a cheese topping. The result was a dish that much resembles what pizza looked like today.

2) The Greeks

The Persians had friendly ally states, including some regions in Greece, throughout and past wartime (and the Persians fought many). As friends, the Persians wanted to ensure their neighbors were fed well. Sharing their quick and simple recipe with the Greeks made sense. Their flatbreads with cheese and other toppings took little time to bake but were also filling. Many believe this is how ancient pizza began to spread worldwide.

Ancient Greeks, when home, had more time to experiment with the dish to make it more flavorful. This was when they introduced toppings like herbs, garlic, and onions.

3) The Romans

The ancient Romans also consumed a variety of pizzas–especially Jewish Romans who ate kosher cookies during Passover. The use of Italian paschal bread, which many now call Easter Bread. While the list of toppings, if any, is unknown, the bread is undoubtedly similar to the base of pizzas we see today.

However, at its peak, the Roman Empire sprawled through most of modern-day Europe and some areas in the Middle East and Africa. Throughout the Empire’s lifetime, it’s thought that populations on the Balearic Islands, the Balkans, the Levant, Catalonia, and Valencia all crafted some form of pizza.

4) Ancient Mediterraneans

Ancient Mediterraneans also ate a version of « pizza. » They consumed a large amount of focaccia, leavened flat-baked bread. Today, many refer to it as « pizza bianca » or « white pizza. » The dish was both savory and sweet and was topped with rosemary, basil, sage, and salt.

5) Other Notable Mentions

Since flatbread with toppings is considered the base recipe for pizza, it’s important to note that countless other regions of the world consumed very similar foods. These populations include the Chinese bing, which consists of a flat or circular bread base. Indians famously ate paratha, a fatty bread mixed with spiced potatoes, a vibrant mix of veggies, meat, and more. They often added curries and fried eggs into servings of the dish.

Additionally, populations dating back to ancient South/Central Asia, those of Finnish background, Germany, and France all ate versions of flatbread with filling or toppings for many hundreds of years.

https://www.hungryhowies.com/article/who-invented-pizza-0

-How to Cook Pizza on a Shield Like a 600 BC Persian Soldier.

https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-middle-east/persian-empire

-Ancient Persians Invented Pizza

https://sdmcphail.com/2016/10/12/ancient-persians-invented-pizza/

-In the 6th century, during the period of Persian Empire, the soldiers of Darius the Great baked some form of bread and covered it with dates and cheese.

https://ottavio.ca/en/the-history-of-pizza/

-PIZZA, HISTORY AND LEGENDS

https://www.lebaccanti.com/en/ba/pizza-history-and-legends-11261

*

Ravioli

L’Iran par sa longue histoire a connu une variété gastronomique qui s’est enrichie aux files des millénaires.

On sait par les anciens récits, que le niveau de sophistication de la cuisine sous la dynastie iranienne Achéménienne (Empire Perse) 549 – 486 av. J.-C., était à son apogée lors des festins.

Les rois achéménides dînaient régulièrement avec sa cour, ses soldats et ses ouvriers.

Et pendant l’Empire Ērānshahr (Empire Sassanide) 224 – 651 apr. J.-C., la cuisine iranienne va encore plus s’enrichir en innovant des nouveaux plats à base de pâte.

Il est vrai que de farcir des feuilles de pâte était déjà commun dans les foyers Mésopotamiens mais l’art culinaire de plier (voire rouler) les feuilles pour en faire des bouchées plus ou moins grandes, en adoptant des formes diverses et aussi bien frites (rissoles) que cuites au four (chausson) voire bouillies (pasta ripiena) se développe sous l’Empire Ērānshahr.

Le premier type, le khushknanaj, est un ravioli farci en forme de demi-lune qui a été frite ou cuit au four, il est fait avec une base de pâte d’amande et contient différents types de farces.

Le second type, le lauzinaj, est lui de forme triangulaire et est aussi fait avec de la pâte d’amande, qui est étalée, coupée en petits morceaux puis imbibée de sirop.

Le troisième type est le sambusaj, qui existe encore aujourd’hui dans une bonne partie de l’Asie, en Inde et dans l’Afrique du nord.

Le quatrième type, c’est le joshparah, un ravioli fait à base d’une pâte farcie puis pochée. Ce type de ravioli est encore présent dans de nombreuses régions, notamment en Asie centrale.

L’arrivée du ravioli en Occident se fait avec la traduction des livres de cuisines Persanes, l’un des traducteurs, traduit le terme sambusaj par les mots ravioli et calisone.

Ainsi, les raviolis font leur entrée dans la cuisine italienne au XIIIème siècle.

Et peu après, les raviolis arrivent en France par le sud, sous le nom ravieles, un type de raviolis farcis avec du fromage, des herbes et du beurre, puis cuits au four, c’est l’un des types de raviolis les plus répandus au monde.

Photos:

27-Raviolis

28-Empire sassanide

-Empire sassanide

http://www.utb-chalon.fr/media/files/Documents_conferenciers/Richard/Sassanides.pdf

-Histoire des raviolis : l’origine perse

https://histoiredepates.net/2014/05/11/histoire-des-raviolis/

-La cuisine de la route de la soie : un voyage culinaire

Aujourd’hui, les historiens de l’alimentation s’accordent à dire que les pâtes sont probablement originaires d’Iran.

https://festival.si.edu/2002/the-silk-road/silk-road-cooking-a-culinary-journey/smithsonian

-Histoire de la cuisine persane

http://cuisinepersane.fr/histoire.html

-L’alimentation des Iraniens de jadis

https://www.revueplume.ir/article_93552_f2ccce90594ebc53fbf1b0a3d065354d.pdf

-La première usine de production de pâtes en Iran

https://foodexiran.com/en/the-first-factory-producing-pasta-in-iran/

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Ravioli

Iran’s long history has seen a gastronomic variety that has been enriched over the millennia.

We know from ancient accounts that the level of culinary sophistication under the Iranian Achaemenian dynasty (Persian Empire) 549 – 486 BC, was at its peak during feasts. Achaemenid kings regularly dined with his court, soldiers and workers.

And during the Ērānshahr Empire (Sassanid Empire) 224 – 651 AD, Iranian cuisine was further enriched by the innovation of new dough-based dishes.

It’s true that stuffing pastry leaves was already quite common in Mesopotamian households, but the culinary art of folding (or even rolling) the leaves into bite-sized pieces of varying sizes, adopting a variety of shapes and forms, from fried to baked or boiled (pasta ripiena), developed under the Ērānshahr Empire.

The first type, khushknanaj, is a half-moon-shaped stuffed ravioli that has been fried or baked, made with an almond paste base and containing different types of filling.

The second type, lauzinaj, is triangular in shape and is also made with almond paste, which is rolled out, cut into small pieces and then soaked in syrup.

The third type is sambusaj, which still exists today in much of Asia, India and North Africa.

The fourth type is joshparah, a ravioli made with a stuffed and poached dough. This type of ravioli is still found in many regions, particularly in Central Asia.

The arrival of ravioli in the West came with the translation of Persian cookery books, one of the translators translating the term sambusaj as ravioli and calisone.

Thus, ravioli made its entry into Italian cuisine in the 13th century.

Shortly afterwards, ravioli arrived in France from the south, under the name ravieles, a type of ravioli stuffed with cheese, herbs and butter, then baked in the oven. It’s one of the most widespread types of ravioli in the world.

Photos:

27-Raviolis

28-Sasanian Empire

-Sasanian Empire

https://history-maps.com/story/Sasanian-Empire

-History of ravioli: the Persian origin

The art of stuffing sheets of dough is already attested in ancient Mesopotamia. However, the leaves are left whole because they are used to make puff pastry pies or not. It was probably in Sassanid Persia, renowned for its culinary refinements, that the idea of folding (or even rolling) the leaves to make more or less large bites developed.

https://histoiredepates.net/2014/05/11/histoire-des-raviolis/

-Silk Road Cooking: A Culinary Journey

Today, culinary food historians agree that pasta probably originated in Iran.

https://festival.si.edu/2002/the-silk-road/silk-road-cooking-a-culinary-journey/smithsonian

-From Ancient Persian Food To Persian Ancient Culture

https://foodexiran.com/en/from-ancient-persia-to-modern-iran-a-journey-through-iranian-food-culture/

-The Mother Cuisine: A Taste of Persia’s Ancient (and influential) Cooking

https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/ancient-prehistory-651-a-d/achaemenids/the-mother-cuisine-a-taste-of-persias-ancient-and-influential-cooking/

-The first factory producing pasta in Iran

https://foodexiran.com/en/the-first-factory-producing-pasta-in-iran/

*

Naan en persan veut dire pain

-Le Pain traditionnel iranien

https://iran-cuisine.com/fr/recipe/barbari-nan-e-barbari-pain-iranien/

-Présentation du pain iranien

https://kindiran.com/fr/Gallery/Iranian-Breads

Photo:

29-Pain traditionnel iranien

✍️ENGLISH ENGLISH ENGLISH

Naan in Persian means bread

Photo:

29-Iran Traditional Bread

-Iranian traditional flat bread

https://iran-cuisine.com/recipe/barbari-iranian-bread/

-Introducing Iranian Breads

https://kindiran.com/en/gallery/iranian-breads